U.S. Naval Academy graduates have always gone the extra mile, in sports, business, the military, and more. So it was fitting that in 1960, USNA graduate Lieutenant Don Walsh made a historic trek to the ocean’s depths, the deepest in history. The stakes were as high as you might imagine, with deep sea diving technology still in its infancy. Walsh and his partner, the renowned Swiss oceanographer Jaques Piccard, were unsure if the apparatus would even work. In fact, Walsh once reported dryly that he was briefing a visiting admiral on the project, who remarked, “Lieutenant Walsh, the Navy does not glue its ships together!” to which Walsh wryly replied, “Perhaps, but ours was glued.”

The Historic Mission

When he accepted the secret mission, code-named “Nekton” in 1959, Walsh did not know what he and Piccard would be doing, beyond just going out to sea. At this point, his deepest dive in a submarine was 300 feet. But for this new dive, the men would descend to the deepest part of the ocean in the Pacific’s Mariana Trench, called the Challenger Depth. It’s about 200 miles southwest of Guam, and it’s 6.7 miles below the surface—more than a mile deeper than Mt. Everest is high—a place no human had ever seen.

The two explorers would be traveling in a bathyscaph called the Trieste, that Piccard and his father had designed and sold to the U.S. Navy in 1958. It was 60 feet long, and a special epoxy kept its steel hull together (the glue to which the admiral referred). There was nothing like it at the time, so Piccard and the Navy engineers needed to start from scratch, designing and crafting cameras, lights, samplers, and sensors. “We were writing the book for deep ocean operations,” noted Walsh.

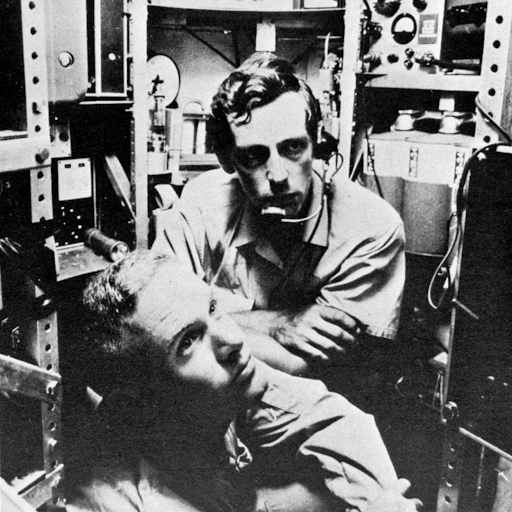

After completing sequentially deeper test dives in 1959, several of the outside instruments failed under the extreme water pressure, but the vessel itself persevered. Then the hydronauts made a dive to 23,000 feet right outside Guam about a week before the historic dive. Walsh and Piccard helped tow the Trieste about 200 miles southwest of Guam. On the dive day, they discovered, with dismay, seawater had entered the chambers and sloshed the equipment around. They tested the electrical systems and electromagnets that were used to release ballast, and these were in working order. “I made the decision,” said Lieutenant Walsh. “We would dive.” So the men fit their frames in a square chamber with only 38 inch sides and a 5’8” height, and the 350-pound hatch was bolted shut.

The Dive

As they descended, the water pressure grew to almost eight tons per square inch, which would spell certain disaster if the vessel didn’t hold. They counted to 32,400 feet, when they heard a muffled bang, a worrisome sound. They couldn’t identify it at the time (it turned out to be a viewing port acrylic glass cracking from a moving metal fixture), but continued into the deep darkness, and after five hours of descent they reached a depth of 35,797 feet . When the lights were on they peered through thick portholes to find fish, shrimp and jellyfish - sea creatures that marine biologists weren’t sure could have existed in such a high pressure environment past 30,000 feet in depth. The men radioed to “Pittsburgh,” the call name for the Wandank. “Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, this is Trieste, we are on the bottom of the Challenger Deep at six-three hundred fathoms. Over,” Lieutenant Walsh said. “Trieste, Trieste, this is Pittsburgh,” responded Lieutenant Larry Shumaker. “I hear you faint but clear.” Neither vessel had expected they would make contact, and the excitement was palpable.

Jaques Piccard and Don Walsh spent about twenty minutes on the dark seabed, observing the area and taking detailed measurements before ascending back, waving an American and Swiss flag and enjoying some chocolate before they were greeted at the surface. Back home, Walsh was honored with a number of awards for his work, including the Legion of Merit by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Hubbard Medal, the National Geographic Society’s highest honor.

Before the Dive

Walsh’s journey to this historic moment started in 1948 when he enlisted in the Navy. He graduated with the U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1954 and commissioned as a submarine officer, later commanding USS Bashaw. After a full career, Walsh retired from the Navy having earned the rank of captain in 1975. He had earned a Master’s of Political Science from San Diego State University and his Doctorate in Physical Oceanography from Texas A&M University. He taught this subject at the University of Southern California from 1975 to 1983.

In 2001, Walsh returned to the depths again on the commercial MIR-2 submersible after he had spent time consulting on films including Raise the Titanic and The Hunt for Red October. He remained fascinated by this subject.

While Walsh passed away on November 12th 2023 at 92 years old, the work he pioneered lives on, and as we focus more on solving the climate crisis, it becomes more critical than ever. Even though a 2019 dive led by explorer Victor Vescovo surpassed his record depth at 35,843 feet, Piccard and Walsh’s feat remains one of the pioneering acts of deep sea observation.

More Adventure Awaits

We honor Captain Walsh’s memory and are grateful to him for his heroic efforts in exploring the seabed (in a vessel “glued” together, no less). Our USNA graduates never cease to amaze us with their bravery and verve as they conquer new frontiers. Do you want to learn more about these fascinating stories? Come see us on the Yard! We offer a number of captivating USNA tours where you can dive deep into the history of this amazing place. Your tours, meals and shopping also give back to the Brigade, so you can support the midshipmen who support us. Proceeds help fund extracurricular activities like cultural arts, music, theater, club sports, and more. We look forward to seeing you on your next adventure!

-1.png)